I've decided that this will be my last entry in The Clayton Series. I'm doing this installment differently. I will be commenting throughout this segment of Clayton's essay rather than at the end. Clayton's words will be in blue. I'm continuing where I left off last time working through the section titled, "Controlling Definitions Means Controlling The Debate":

Clayton: ... I think that most Christians, when they are allowed to give the definition of the term, define [faith] incompletely. When a non-theist defines the term, it usually sounds something like this: faith is believing in something without evidence. I respectfully reject that definition.

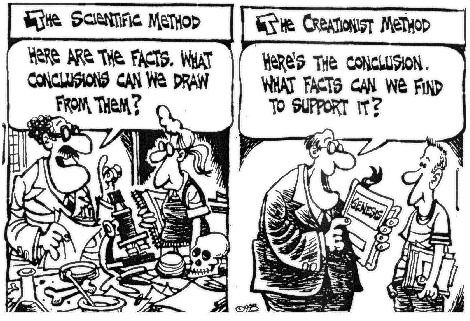

Bud: A more accurate definition of "faith" is belief irrespective of evidence. Most people who come to faith do so apart from any rational reason. Few religious people - if any - came to faith via rational scrutiny of evidence and logical argumentation. Even those who accept faith for "reasons" don't have reason as the basis for their decision to convert. Those who, after already converting, desire to be (or appear) rational will begin searching for reasons to believe (or continue believing), but there's a huge difference between arriving at a conclusion through reason and attempting to use reason to justify a conclusion one's already accepted. Reminds me of this comic:

Clayton: The most common definition for faith that I have heard from Christians is from Hebrews 11:1; 'faith is being sure of what we hope for and certain of what we do not see.'

Bud: There's a reason why it's the most common definition. Most Christians see faith as justification in itself. "How do you know god exists?" "Because I have faith."

Clayton: This isn't incorrect, but it is incomplete. It would be like me saying, "Lisa is my wife." The statement is true, but it is incomplete. Lisa is so much more than my wife, and if I were to attempt to completely define or describe her, I would have to say much more. In some ways, trying to define faith is like trying to define a human being, it is difficult to do because it is a thriving and growing thing, continually changing and different from person to person.

Bud: Indeed, how faith is defined differs from person to person, and I'll add from group to group. What Clayton misses in his attempt to define faith is that non-theists aren't trying to redefine the word in order to win debates or score points for "our side." We're simply reacting to how the religious folk we've encountered define - and live out - faith. We didn't make up that meaning of faith; it was thrust upon us, and we reacted accordingly. And let's go back to Hebrews 11, shall we? "Without faith it is impossible to please God" (Hebrews 11:6). Faith is the opposite of doubt, and doubt is required to think critically; therefore, faith is contrary to critical thinking, which means critical thinking is contrary to God's happiness. I didn't make this up. I come from a Christian background, and this is how most Christians live out their faith.

Clayton: I want to differentiate between two kinds of faith, both of which are seen as virtues in Christianity. The first kind of faith is simply belief. In the Christian religion this means accepting the propositions of Christianity as true. A lot of people have a hard time seeing this as a virtue because we do not see believing that anything else is true as virtuous. Belief comes when a conclusion is drawn from reason after an analysis of evidence. For some people the evidence is simply, 'I have heard it on authority'. In other words, my parents told me to believe it, and so I do. I know that many people believe that this is the engine that Christianity is driven on, but that is not entirely true. It is true in the sense that there are a lot of Christians whose faith is borrowed from their parents, or another authority, but there are also those like myself who have come to faith later in life without the involvement of any such authority. In fact there was a time that all Christians were that way.

Bud: There was a time all Jehovah's Witnesses and Mormons and Muslims and Jews were that way too. All it takes is one person with a "message from god" to form a small group of zealots who subsequently start making converts of their own. A preacher becomes a cult which becomes a movement which becomes a religion - as long as they get enough converts (and the cult leader doesn't have all the followers drink the poisoned kool-aid so they can reach the mothership or some other such nonsense). Religions like Christianity maintain a strong influence because of the fact that faith is passed down from parent to child. The indoctrination process begins at a very young age, before the child can do any kind of rational analysis of the teachings. How is this a virtue?

Clayton: The virtue of this kind of faith comes from holding to a belief that you have come to believe is true even in the face of, not contrary evidence, but a contrary mood. Most people who come to accept Christianity as true will inevitably go through a crisis of faith. Sometimes, albeit rarely in my experience, this crisis comes from conflicting evidence gained through reason. More often this crisis comes in the form of a depression, a feeling of abandonment, an attempt to cope with a tragedy or trauma, or a personality conflict with another Christian, particularly a Christian leader, or it comes during a time in adolescence characterized by rebellion. Then, this experience which is almost entirely emotional in nature, leads a person to reject certain premises that were accepted before the mood and accept other premises that were rejected before the mood based on the difference in... well, mood. I know that it is a common thought that most people accept Christianity on an emotional basis, it is my belief that most people reject Christianity for the same reason.

Bud: I'm sure many people reject Christianity for emotional rather than intellectual reasons, because virtually all Christians accept Christianity for emotional rather than intellectual reasons in the first place. I find Clayton's observation here to be mostly irrelevant. How many people left Christianity for emotional reasons isn't the issue: the relevant concern is whether there are any rational or intellectual reasons to accept - or reject - Christianity.

Clayton: It is absurd to believe that our conclusions are based entirely on reason.

Bud: I agree, but let there be no misunderstanding: reason is mandatory. To quote Hitchens: "Our belief is not a belief. Our principles are not a faith. We do not rely soley upon science and reason, because these are necessary rather than sufficient factors, but we distrust anything that contradicts science or outrages reason. We may differ on many things, but what we respect is free inquiry, openmindedness, and the pursuit of ideas for their own sake." We consider reason to be a necessary condition rather than a sufficient condition. And since we're on the subject of faith, I have to ask: when does faith find harmony with the notion of free inquiry, openmindedness, and the pursuit of ideas for their own sake? Never.

Clayton: Everyone has observed in other people the tendency to want to believe or disbelieve something about a person, or a food, or an organization, based more on emotion or fashion than on reason. But most people are very hesitant to acknowledge any such tendency in themselves.

Bud: I agree again, and believe that if Clayton truly understood the logical implications of his words, he would be well on his way to accepting agnosticism and a step closer toward discarding his religion.

Clayton: What I take in influences what comes out. If I am led to prefer a lifestyle that rejects traditional Christian values by my environment, the likelihood of me rejecting Christianity rises considerably. This is the reverse of the 'there are no atheists in foxholes' idea. People in danger are comforted by the idea that there is a God, and their likelihood to believe that it is true rises dramatically. People in the midst of a materialistic culture discouraging chastity, selflessness, peace and patience are more likely to reject a religion that holds those things as virtuous.

Bud: I wonder whether Clayton is subtly dissing atheists here. He says people in the midst of a "materialistic culture" (whatever that means) discouraging chastity, selflessness, peace and patience are more likely to reject a religion that considers those virtues. I'm not sure of the "culture" to which he's referring. Atheist culture? Let's be clear that the current atheist culture may not be so worried about chastity (instead focusing on proper sex education and proper health and protection, which interestingly religion has prohibited over the years centuries), and patience is a virtue insofar as it doesn't evolve into complacency, but most folks representing the atheist community place a great deal of value in peace and selflessness, as well as kindness, love, and compassion.

Just so we're clear on this.

Clayton: The Christian virtue of faith in this first type is to keep in mind the beliefs that we have accepted to be true. Belief needs to be fed to be immune to mood changes. To put the primary beliefs of Christianity in front of you daily, to repeat them, to say daily prayers, to read the Bible every day, all help to guard this kind of faith. It is a virtue to hold onto things that you believe to be true in spite of your environment. I cannot imagine that a freethinker would disagree.

Bud: I disagree. Why should belief "need to be fed" at all? Let me borrow the words of Dan Barker, who said: "Truth does not demand belief. Scientists do not join hands every Sunday, singing, yes, gravity is real! I will have faith! I will be strong! I believe in my heart that what goes up, up, up must come down, down. down. Amen! If they did, we would think they were pretty insecure about it." Belief only needs to be "fed" is it lacks a solid foundation of reason to support it. Regardless of what mood I'm in, I won't suddenly reject the theory of gravity.

Clayton: A second type of faith is derived from the Greek word pistis. Anytime you see the word 'faith' or 'believe' in the New Testament, it is from pistis. The reason it isn't always translated as 'faith' is because we have no verb form for that word in English. People don't go around 'faithing' things. So the word 'believe' is chosen instead. This is unfortunate, because it gives the false impression that instances of this second type of faith are actually instances of the first kind. The best and simplest explanation that I have ever heard for pistis is this:

Faith = Belief + Obedience

This is the idea that you believe something to be true, and strive to live in accordance or conformity with that belief. In this form, I am hard-pressed to understand why anyone would deny this as a virtue. I believe that my wife is not having an affair, that she is telling me the truth when she says that she is at work, and not with some other person. I cannot prove this to you. I cannot demonstrate empirically that this is true. I can only have faith. Now, there may be a time when I am presented with contrary evidence that may cause me to reevaluate that faith, but until that time comes it would be foolish of me to not strive to live in accordance with what I believe to be true.

Bud: No one is denying that "living in accordance with what one believes" is a virtue. This section ignores the heart of the matter; namely, how faith is really lived out by the faithful. They aren't simply "living according to what they believe": they are doing so at the cost of reason, by ignoring or twisting the facts in order to maintain their faith.

What bothers me even more is the implicit proposition throughout this section that everyone, whether theist or non-theist, has "faith." Seems like another attempt at leveling the playing field.

Clayton: I think a significant portion of the frustration associated with the idea of faith comes from those who have encountered Christians who are unwilling to consider evidence that is contrary to their faith. I agree that this is frustrating.

Bud: It's not just a "significant portion": it's just plain why we reject faith. Believers, acting "in faith," reject or ignore evidence contrary to their belief.

Clayton: To completely write off or deny evidence that is contrary to your current beliefs because of the fear or discomfort associated with doubt isn't faith; it's anti-intellectualism, or stubbornness, or foolishness.

Bud: Like I said, how faith is defined differs from one person to the next. When I was a Christian, I didn't define "faith" that way. I considered myself a freethinker, which is why I'm an atheist today. I considered the evidence for Christianity, and found it lacking severely. Perhaps Clayton doesn't see his faith as contrary to critical thinking. I can't speak for him. I know, in my own case, my faith held me back. Even as I extolled the virtues of critical thinking when I was a Christian, I wrestled with compartmentalization and cognitive dissonance. I wrestled for years until I was able to dislodge myself from faith and truly follow reason.

For most Christians (whether they realize it or not), faith is equivalent to anti-intellectualism, stubbornness, and foolishness, as well as wishful thinking and unfounded hope.

Clayton: I think that it needs to be acknowledged that this tendency is present on both sides of the theism debate, but I take it as true that it is more commonly found among Christians than non-theists. The problem isn't faith, it's a lack of education.

Bud: Yes, there are folks on both sides of the ideological fence who base their views on something other than reason. Yes, this is more prevalent among theists than non-theists. And yes, the problem is a lack of (proper) education. Of course, the lack of good education has lead to the longevity of faith.

Dead-Logic.com